New paper & film | First photos of oceanic manta rays in Fiji

The last few months have been pretty intense, with lots of different assignments, travel and the usual daily ups and downs. After three years in Fiji, I flew home to Germany in May for a much-needed visit to see friends and family. And in August and Amanda and I had another trip to Europe in August, this time starting in the UK and then heading to Germany to sort our storage locker (four years ago, we planned to sort it out within six months), reunite with friends in our old home Bremen, and celebrate my brother's wedding in Cologne.

Finally back at science (in between my day job)

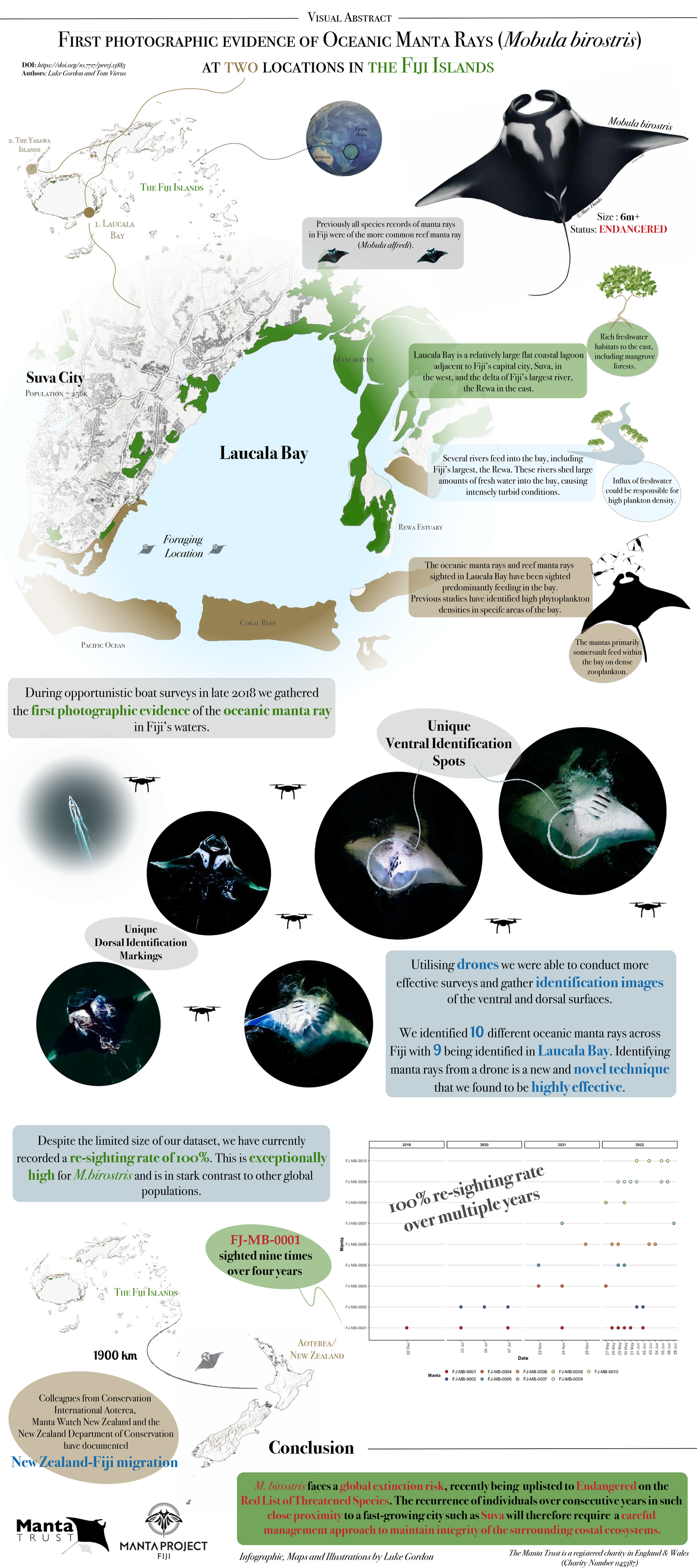

But back to the actual topic of this post: our new paper published in PeerJ. To put it into a bit more context, we have to go back to 2021. Back then, my good friend Luke Gordon from Manta Project Fiji, a subsidiary organisation of Manta Trust, and I were chatting about a potential paper that would discuss the occurrence of oceanic manta rays (Mobula birostris) in Fiji. Despite being the largest ray in the oceans, there hadn't been any photographic proof or scientific articles mentioning them within Fijian waters. This was partly due to the (repeated) re-structuring of the Mobula and Manta genus, including the resurrection of a new manta ray in 2009, when scientists discovered that the one manta ray species known up to that point was actually two separate ones: Manta alfredi (the reef manta ray) and Manta birostris (the oceanic Manta ray). The restructuring didn't stop there, though: based on new findings, the scientific consensus moved the manta rays from the Manta genus into the already existing Mobula genus, changing their nomenclature from previously 'Manta' to now 'Mobula' rendering past records unclear and basically unidentifiable.Long story short, we knew something had to be published in order to scientifically anchor these findings and make them publicly known. Conservation measures can only be implemented and managed when a) we know a species is definitely living in an area and b) this knowledge is, in turn, known by decision-makers and turned into actual conservation measures on the ground.The oceanic manta ray is classified as 'Critically Endangered' by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and needs all the help it can get to preserve them for many future generations to come. The main threats to these rather gentle giants is pre-demonantly overfishing and boat propeller strikes which pose a significant threat to the rays during their surface feeding.

This was partly due to the (repeated) re-structuring of the Mobula and Manta genus, including the resurrection of a new manta ray in 2009, when scientists discovered that the one manta ray species known up to that point was actually two separate ones: Manta alfredi (the reef manta ray) and Manta birostris (the oceanic Manta ray). The restructuring didn't stop there, though: based on new findings, the scientific consensus moved the manta rays from the Manta genus into the already existing Mobula genus, changing their nomenclature from previously 'Manta' to now 'Mobula' rendering past records unclear and basically unidentifiable.Long story short, we knew something had to be published in order to scientifically anchor these findings and make them publicly known. Conservation measures can only be implemented and managed when a) we know a species is definitely living in an area and b) this knowledge is, in turn, known by decision-makers and turned into actual conservation measures on the ground.The oceanic manta ray is classified as 'Critically Endangered' by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and needs all the help it can get to preserve them for many future generations to come. The main threats to these rather gentle giants is pre-demonantly overfishing and boat propeller strikes which pose a significant threat to the rays during their surface feeding.

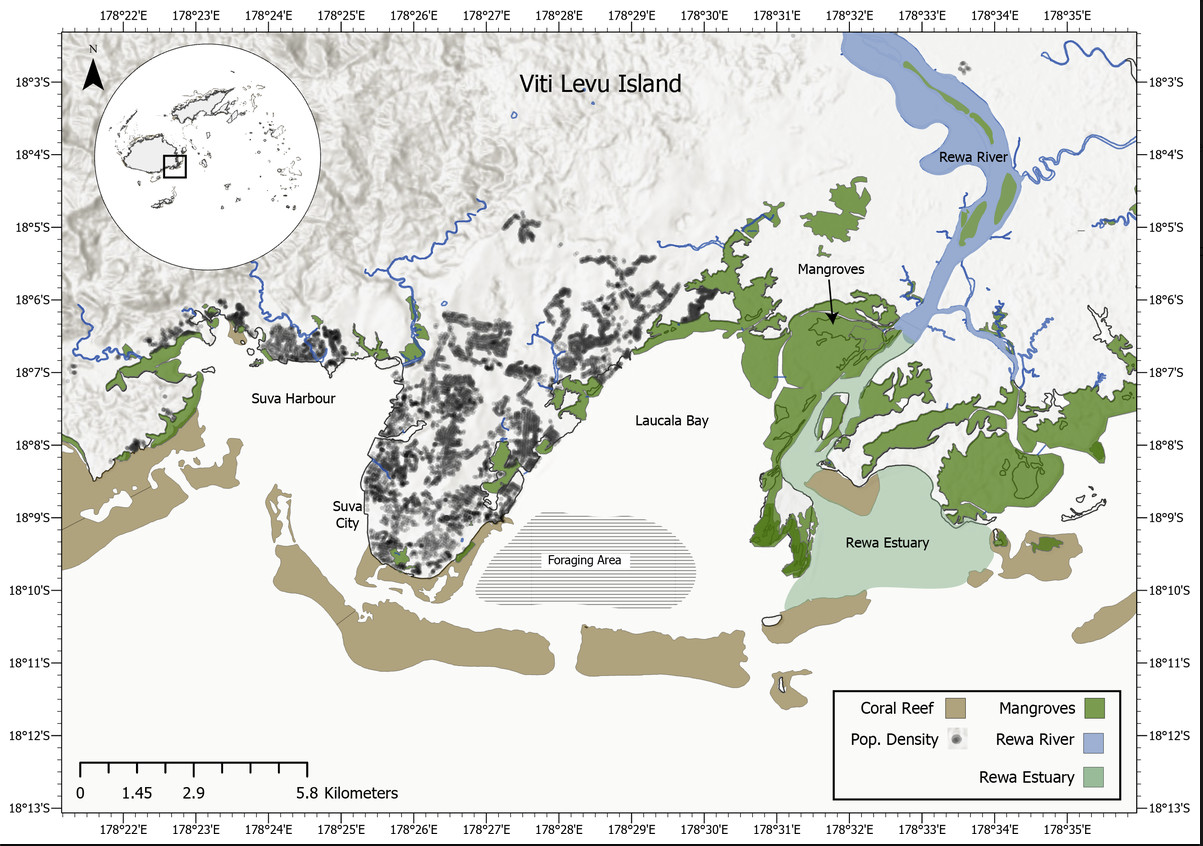

Oceanic Manta Rays right off Suva, Fiji's capital

Laucala Bay is a large bay right next to Fiji's busiest population centre and capital city of Suva and, surprisingly, home to what appears to be an important feeding site for oceanic manta rays as well as their slightly smaller cousins, the reef manta rays. On several surveys, we documented their appearances using a drone, which allowed us to scan large areas with very limited manpower (i.e. just us two), trying to capture the unique identification that appears on their belly (similar to a fingerprint in human beings these spot patterns are unique for every single individual). Eventually, we were able to identify and photograph nine oceanic manta rays in the bay, of which all nine have been re-sighted since. A re-sighting means that the same ray was spotted in the area on a different day. The mantas would often be feeding on plankton very close to the surface. This is often done by a behaviour termed barrel-feeding, where the manta repeatedly somersaults to maximise the plankton intake guided through their large lobes. This is the best time to capture their bellies, as the alternative would be the do so from within the water, but Laucala Bay, due to a large number of riverine inputs, is naturally a very murky environment.Fast forward a few months and the rather tedious process of writing and publishing a scientific paper, we have summarised our findings, analysed them by incorporating all available data thus far and discussed them in light of national and regional conservation initiatives and available data. Thanks to Manta Trust, we could publish the paper as open-access, making it possible for everyone to read it. Follow this link to find it on PeerJ.

Eventually, we were able to identify and photograph nine oceanic manta rays in the bay, of which all nine have been re-sighted since. A re-sighting means that the same ray was spotted in the area on a different day. The mantas would often be feeding on plankton very close to the surface. This is often done by a behaviour termed barrel-feeding, where the manta repeatedly somersaults to maximise the plankton intake guided through their large lobes. This is the best time to capture their bellies, as the alternative would be the do so from within the water, but Laucala Bay, due to a large number of riverine inputs, is naturally a very murky environment.Fast forward a few months and the rather tedious process of writing and publishing a scientific paper, we have summarised our findings, analysed them by incorporating all available data thus far and discussed them in light of national and regional conservation initiatives and available data. Thanks to Manta Trust, we could publish the paper as open-access, making it possible for everyone to read it. Follow this link to find it on PeerJ.

Science without communication = fail

After a finished my master' degree in Tropical Marine Ecology and finished writing up my theses on the sharks of Ba here in Fiji, I was at a crossroads in my life; continuing a career in academics in the form of a PhD or committing myself to full-time visual storytelling and science communicating.Due to a number of factors (including the winning of the German Prize for Science Photography with a series of images depicting my shark research in Fiji and the resulting media interest in sharks and my work), I eventually decided on the latter path. And although I do miss actual scientific work (especially in the field) and have occasional doubts about past life decisions, I love what I am doing and think it was the right decision. I am mentioning this here, as it was paramount for Luke and me not only to publish the paper but also to communicate it as far and wide as we could. To me, this is where conservation science (and storytelling) really begins: it is not only about finding and writing up the data but actually using that information, distributing it far and wide and (hopefully) effecting change by doing so.To that end, I produced a film interviewing Luke about his work and the exciting occurrence of oceanic manta rays just off Suva. Take a few minutes and watch the film, which was also accepted to the Wildlife Conservation Film Festival later this year in New York, below.[su_youtube url="https://youtu.be/RbbsaAnYaOM" width="400" height="300" mute="yes"]

And although I do miss actual scientific work (especially in the field) and have occasional doubts about past life decisions, I love what I am doing and think it was the right decision. I am mentioning this here, as it was paramount for Luke and me not only to publish the paper but also to communicate it as far and wide as we could. To me, this is where conservation science (and storytelling) really begins: it is not only about finding and writing up the data but actually using that information, distributing it far and wide and (hopefully) effecting change by doing so.To that end, I produced a film interviewing Luke about his work and the exciting occurrence of oceanic manta rays just off Suva. Take a few minutes and watch the film, which was also accepted to the Wildlife Conservation Film Festival later this year in New York, below.[su_youtube url="https://youtu.be/RbbsaAnYaOM" width="400" height="300" mute="yes"]

Infographics and other oceanic manta ray outreach

Another path of communicating our findings was through a visual abstract or infographic, which you will find below. What it basically does is summarise the entire scientific publication in a visually appealing way. This way, we hope to reach many more people. People who would not necessarily read an entire paper but would still like to know the main takeaways of it. Have a look through this beautiful infographic (and download + distribute it) that Luke made: Thanks to Melissa Cristina Márquez, shark scientist, author, and science communicator, Forbes published an article summarising our research. Find it here or click on the image below.

Thanks to Melissa Cristina Márquez, shark scientist, author, and science communicator, Forbes published an article summarising our research. Find it here or click on the image below.